In recent decades we've seen a revival of interest in the devotional use of icons in the West, and I like to think that icons are doing more to bring about mutual understanding between Eastern and Western churches, and heal the great Schism of 1054, than a thousand years of conferences and theological debate. People are also experiencing a revived taste for the more austere artistic styles of the pre-Schism era. It is a valid argument that too much surface 'prettiness' is a distraction from the inner meaning and true purpose of the image. So human nature being as it is, debates over what constitutes a 'real' icon tend to rage, with combatants proclaiming one style spiritually superior to another according to their personal aesthetic and/or cultural bias. A cautious glance into the online discussion forums reveals furious verbal coshing about who should be permitted to paint icons and how, and much finger-wagging and invocation of church Canons about the making of them, None of these 'Canons' actually exist. Theologians of the early church discussed the use of the image, and certain conventions and guidelines have come down to us through tradition and painters' manuals, but no hierarch ever actually sat down and wrote a rule book. Whilst I have my own thoughts on the spirituality and practise of iconography, I love the words of St John of Shanghai and San Francisco (1896 - 1966) which I recently ran across: "I can pray in front of this kind of icon; I can pray in front of that kind of icon. The important thing is that we pray, not that we pride ourselves on having good icons."

Another technical difference between the two styles is in the underpainting of the flesh. When painting in a 'Byzantine' style I shade the flesh with dark olive green, paint a tawny flesh tone over that topped by white highlights. The shading is less blended, the highlights often quite stylised. The effect also tends to be of a swarthier, mediterranean skin. In my 'Italianate' icons I shade with sepia and cover the flesh areas with a layer of cool green earth. Skin tones and highlights are painted over the green, and the effect is more of a paler, causcasian skin. This green underpainting of the flesh is very characteristic of medieval and Renaissance art: often the pink pigment used to put the roses in the face of the maddonna and angels has faded away leaving them looking a bit ill and anaemic. I wrote about this 'green sickness', and tooled gold work, in another blog post here. In short, when I say 'Italianate', I intend nothing more than to indicate an iconographic style which is very popular with some and anathema to others, without - I hope - offending either. I will continue to experiment in the style, although the labour for the elaborate gilding is immense and one cannot really charge for the time involved. So to finish with a little seasonal celebration, here are a few of the paintings I have labelled as Italianate or Sienese over the years. I just viewed another wonderful video by Attila Gazo of www.masterpigments.com about the production of blue pigment from mineral azurite. Find it here on YouTube by cut and pasting the link in your browser: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OcMCGNNzxtk.  A divine colour, azurite, as important in later medieval western art as lapis lazuli. If I could afford to, I would splash it on all over. I love it in its purest grades, as in this tiny illuminated letter T (back of a pendant jewel I made for my daughter): - - and just as much in its lesser grades, as the greenish shade I used for Christ's robe in this icon of the Confession of Thomas. I once harboured ambitions to make my own pigments, but just looking at the equipment and repetitive processes involved in Attila's work is enough to make one come over faint. Quite a risky business too, given the toxicity of some of these pigments. Check out his videos on the production of lead white and cinnabar.

Recently a family member asked me to provide some artwork for the cover of a forthcoming book, which besides being my first opportunity at a project of this kind presented some interesting technical problems. Gold areas in a design are notoriously difficult to reproduce in print. Every scratch and blemish is magnified in a scan, it comes out looking dull and brown, or gives off unwanted reflections. I decided it would be a waste to include any gold in the design at all. Not that lack cheapens the piece as an icon in any way. In the past, icon painters by no means always used gold in their designs. In times of scarcity or of war, for fresco schemes, for clients with shallower pockets, or sometimes simply for artistic reasons, many icons were painted with coloured backgrounds. Putting aside its symbolical properties, burnished gold acts as neutral in a painting (strangely enough) and also, as a background, makes a motif 'tell up' incredibly well. Also, let's be honest, that amount of bling tends to distract from a multitude of shortcomings in a painting. Icon painters can tend to get very hung up on the quality of their gilding and devote less time to improving the actual painting!

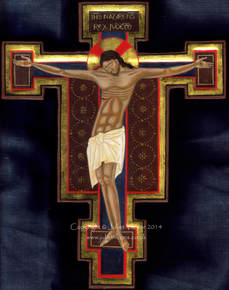

In the end I substituted a painted ground of red for the the medallion of Christ. I added the symbols of the four gospellers afterwards, to complete the piece as an icon, and used brilliant white for the background. White is used in icons to convey the brilliance of uncreated light (think of Christ's robes in icons of the Transfiguration). I would have made life a great deal easier for myself if I had not glazed the red with transparent quinacridone pigment to warm its tone - forgetting that quinacridone is horribly staining and travels everywhere, especially onto pure white backgrounds! The quinacridones are a new addition to the artist's palette, developed by the car industry I am told, and useful as a substitute for carmine and alizarin, which are of suspect lightfastness. It's just too darn messy, though; I think I shall have to retire it from my arsenal. An icon of Christ the Teacher in combination with the Hindu and Buddhist lotus symbol were specifically requested by the author to tie in with the theme of the book, which is a work of comparative theology. I designed the roundel of Christ to appear within the 'O' of the book title, with the eastern lotus symbol and frieze beneath, though no doubt the publisher will rehash my design to his own taste. I believe the book goes to print quite shortly: publisher James Clarke & Co Ltd. The actual icon will be framed (unusual for me, but for purposes of reproduction the board was a lightweight one), and appear for sale on my website in due course. Gold is yellow, right? Well not really: some golds are more yellow than others. The two icons of St Francis above are looking like one of those 'spot the difference' puzzles we used to get as children, but the chief difference - the colour of the gold leaf I used in each - is not at all obvious on the screen. When you go to buy a book of gold leaf - generally from an on-line supplier - the array of golds on offer is completely bewildering. Bog standard 'yellow' gold can be 24, 23 or 22 carat, extra thick, double thick or regular, and each differs slightly in its tone. Not enough difference to read on a computer screen perhaps, but very obvious if you accidentally mix them up on the same painting (yep, been there!). Then there's Italian gold, German ducate, moon gold, red gold, lemon gold, green gold, champagne gold, white gold - the computer screen doesn't give one a very good idea of the differences and sample books are very expensive. The different colours are determined by the quantity and type of alloy metals in the leaf - silver, copper, nickel etc. 24ct gold, being pure, is a rich yellow colour; 22ct tends to be slightly more silvery. Some gold leaf has more of a crinkly texture, which you may or may not like. The presence of copper in the mix makes the leaf appear pinker (one sees this reddier tone clearly in gold jewellery made in India, for example).

So how to choose? Well, anything below 22ct is likely to tarnish fairly quickly, so is best avoided for work that you want to last: that instantly eliminates quite a number of options offered by the goldbeater. 24ct gold is more malleable and does not tarnish at all, so is chosen for 'best work' and for anything that will be exposed to the outside air. It is softer and therefore show the joins between leaves less after burnishing. Using 'double' or 'extra thick' gold leaf may mean you can avoid double gilding, which is generally necessary in order to get a good finish with standard thickness leaf: it is more expensive than standard thickness, so you will have to calculate whether with luck and skill you will make a saving or end up having to double gild anyway! For work intended to stay indoors, so less exposed to atmospheric pollution, 22 ct is adequate and perhaps a little easier to handle on the cutting pad. Beyond those parameters, you can let your choice be dictated by personal taste and price. The second of my St Francis icons (dated 2017) was made with 23 ct red gold, which I bought this time for no better reason than that it was older stock being offered at the old price. I like the way its warmer tone sits with the reds and browns of the icon - I have yet to decide whether it will sit comfortably in other pieces.

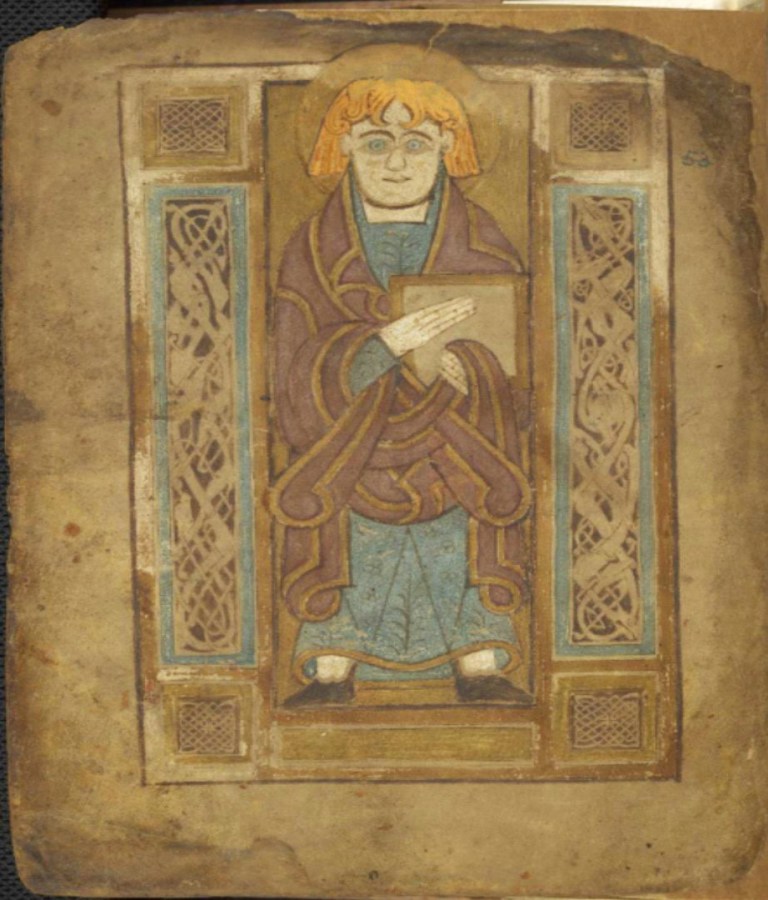

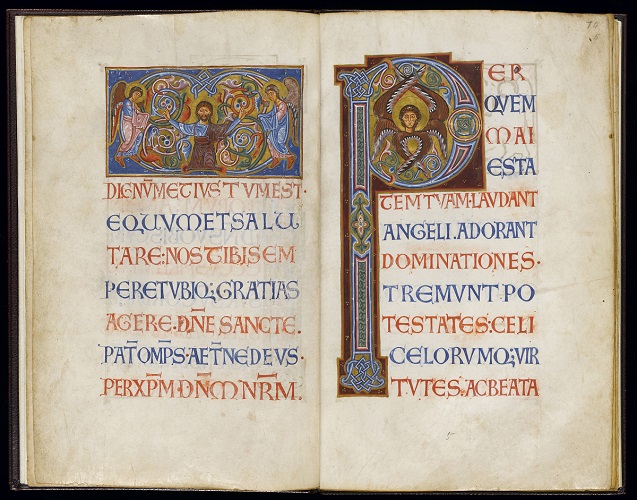

I was hard put to it to decide which beautiful picture to use as an illustration of my recent visit to this exhibition and eventually decided on this page from a Latin Kingdom of Jersusalem sacramentary, dated around 1128. I love it for the east-meets-west style of the icon panel, and the beautiful versal script. I am learning how to write versals at the moment, this is definitely one to add to the study list.

A must-go exhibition for iconographers, illuminators and scribes - on till December, so don't miss. Many of the manuscripts are in cases of course, giving the usual difficulty for close examination, but there are many cuttings framed on the wall which one can eyeball closely. There are also handy reference copies of the £30 exhibition catalogue lying everywhere, which means one can examine photographs and read up on detail without expense. Give yourself a good couple of hours and try to get there early before the usual headphone brigade are there blocking the view! Many of the manuscripts are from the University collection, but there are also borrowings from the British Library, the Archbishop of Canterbury's Library and elsewhere. The later medieval and early Renaissance period is quite heavily represented, as one might expect. The show's chief focus is on the chemistry and provenance of pigments and materials used in book illumination but technique is also touched on. Iconographers will be interested to study the gradual development of different fleshpainting techniques, from the fully modelled style of the Byzantine period through to western experiments with pointillism, grisaille and tinted drawing. Other random gleanings that I shall follow up on my next trip: - Different ways of ruling the page: pricking, hardpoint, silverpoint, plummet. Medieval readers preferred their pages to be ruled and even drew in guidelines to the first printed books because the page looked naked without! So this business in calligraphy class about not showing the lines is a load of rubbish, ha! - Using black gesso under gilding for special effect. Must try, could look amazingly contemporary. - Indigo and woad are chemically indistinguishable when used as dyes or pigments. Western artists probably used woad. It will grow in the back garden, and I found someone on line who extracts and sells the pigment. - The fabled Tyrian purple, so expensive, was extracted from North Atlantic dogwhelks as well as from the Mediterranean murex. The farthest Scottish islands had a trade in it. On the other hand there was a cheap subsitute to be made from the turnsole plant or a variety of lichen, used on some of those glorious purple-dyed manuscripts. - Some French manuscript fragments c 1250 were described as having a 'stained glass palette', an artistic cross-fertilisation from the contemporaneous technological developments in coloured glass (remember that amazing Chartres Cathedral blue?). One of the pigments used was minium. I have always held off using minium (red lead) on the grounds of it being so toxic, but I suppose that's a bit daft given that I already use vermilion (mercury), white lead (for gesso) and the cadmiums. I am interested in this manuscript school, and up till now have had to guess at what pigments were used to achieve the effect.

This stuff is precious, I knew that, but toxic too as I heard today on BBC Radio 4 (report here). Today I have been applying it to vellum for a fine illumination commission. Lapis (ultramarine - 'beyond the sea blue') comes from modern day Afghanistan, which as everyone should know is located just south of the Garden of Eden on the medieval world map. Now I hear that the lapis mines are being stripped and the millions raised disappearing into the pockets of corrupt officials and the Taliban. Other deposits of lapis have been found since ancient times, in Chile I believe, but the stone is inferior. There is nothing to replace that extraordinary blue: azurite is beautiful but very green in tone. I suspect when one scratches the surface there is going to be nothing particularly wholesome about the way any pigment is extracted or manufactured, but for now I shall be refraining from smearing lapis all over the icons.

|

The view from my deskCurrent work, places and events, art travel, and interesting snippets about Christian icons, medieval art, manuscript illumination, egg tempera,, gilding, technique and materials. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed