It's not often I find myself in the vanguard of business innovation, so I was really pleased to hear a discussion about the popularity and success of buying art over the web on BBC Radio 4 this morning. I started selling paintings from my website back in 2009 - I think this little crucifix (now somewhere on Orkney) was one of the first commissions I received by internet. I have always been surprised and delighted that people are prepared to buy something so personal as an artwork 'sight unseen'; though the ability to email a high resolution photographic scan is really helpful, and I haven't yet had a buyer ask to return a painting. And my experience is mirrored higher up the feeding chain - apparently on line sales of art have been increasing across the board, even in the four and five figure bracket, and with giants such as Sothebys and Christies. This is a wonderful thing for artists because, provided one can get to grips with the intricacies of on line marketing, it opens the world up for sales and liberates us from selling solely through brick-and-mortar galleries. People are always shocked to hear that an art gallery generally takes 50% of the sale price of a piece, plus VAT on top of that. In London that fee would often be 60% or 70%. Rent and rates on high street premises, glossy brochures and travelling to art fairs and functions all costs a great deal of money even before the gallery's staff costs are paid. It is very hard for a gallery owner to make a living. Unfortunately it is even harder for an artist. To make more than five pence an hour painting an original, an artist's work must command a very good price indeed, involving years spent slowly building a 'name' and nudging up ones prices. A gallery's commission is only the start of the expenses involved in selling. The artist bears the cost of professional framing - if you have ever had a print framed, you will know how expensive that can be. A gallery takes work 'on consignment' - that is to say, the artist is paid nothing for it until it sells, if at all. Often an artist has to pay an up-front annual fee for wall space before the gallery will actively market the work. As a result, many galleries are stocked largely with prints or cheerful-looking canvasses with rorschach blobs and splashes. So dear reader, if you are buying art for your home and want something really original and unique I urge you to become a patron of the arts. Hunt down the artist's website and approach them directly. No prices displayed? It costs nothing to ask! Some new bird-in-letter pieces for the new season. They will be sold individually, which is just as well because I see if I switch them around they will spell 'SOB', which was not what I intended...

The window as a whole is very large and elaborate in conception, and there are more expensive stained glass windows lining the nave, though Troutbeck is such a tiny place you could blink and miss it - Troutspeck, even. I guess the grandees who commissioned the many fabulous Arts and Crafts or neo-gothic holiday palaces in those parts were gracious enough to share some of their worldly excess with the local yokels who joined them for worship in these little village churches.

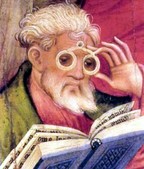

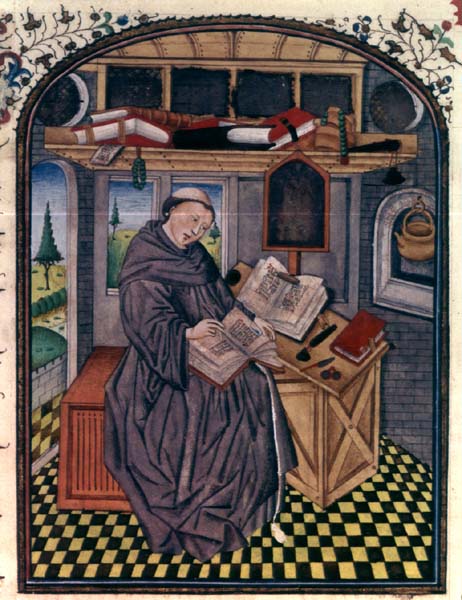

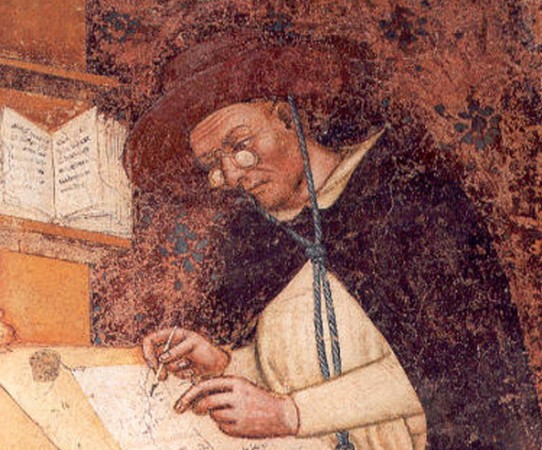

I don't think the effects of myopia - or even astigmatism or cataracts - on a person's life have been given proper credit by art historians. Most illuminated manuscripts have details so tiny that the artist must have had magnifiers or have been naturally shortsighted to paint such tiny detail so perfectly: reproductions in books tend to be enlarged so one doesn't get a true impression of how tiny they were. I've always been very short-sighted myself, and when I take off my glasses I can see in glorious magnification provided I have my work no more than an inch from my face. Anything further away is a miasmal mist, so that I have to line up my pigment pots in a special order and locate them by feel. I am exploiting my own weakness by choosing to paint small, but if I wanted to go larger it would have to be as a latter-day misty Impressionist or a new Jackson Pollock. Easel painting would mean constantly juggling with three sets of eyewear.

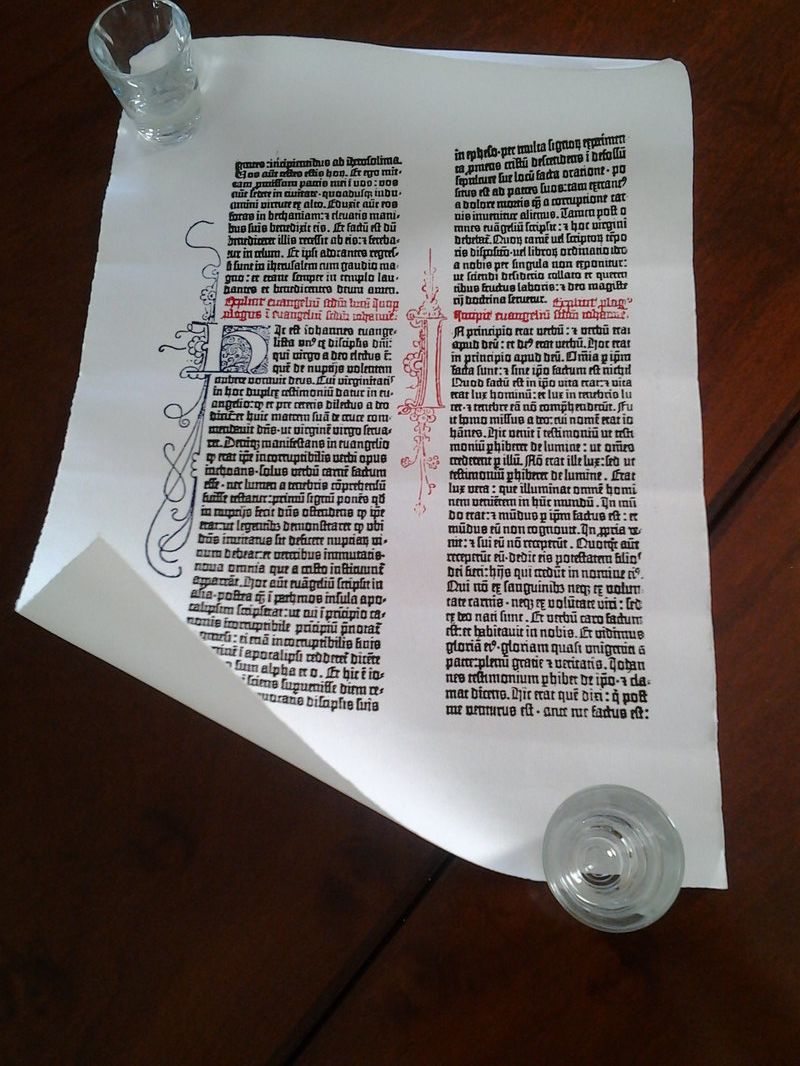

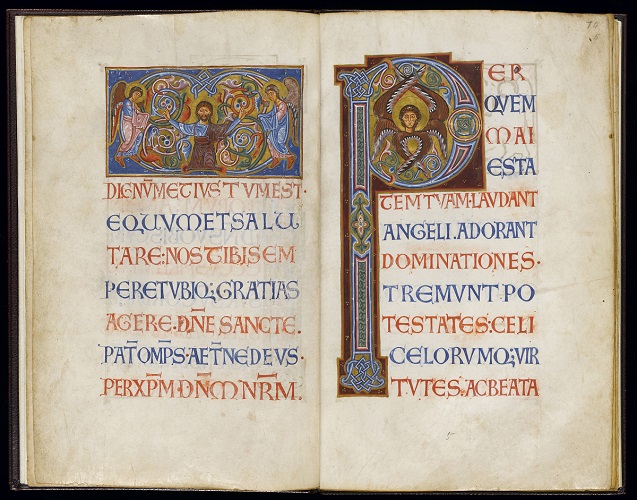

Getting back to Gutenberg and his printing press, the Museum was very empty when I visited so I was lucky enough to get a turn printing a page of St John's gospel on his very machine. So exciting! The machine actually started out life as a wine press, which Gutenberg adapted to the purpose. An incredibly heavy contraption to turn- his assistants must have been a brawny bunch. I was hard put to it to decide which beautiful picture to use as an illustration of my recent visit to this exhibition and eventually decided on this page from a Latin Kingdom of Jersusalem sacramentary, dated around 1128. I love it for the east-meets-west style of the icon panel, and the beautiful versal script. I am learning how to write versals at the moment, this is definitely one to add to the study list.

A must-go exhibition for iconographers, illuminators and scribes - on till December, so don't miss. Many of the manuscripts are in cases of course, giving the usual difficulty for close examination, but there are many cuttings framed on the wall which one can eyeball closely. There are also handy reference copies of the £30 exhibition catalogue lying everywhere, which means one can examine photographs and read up on detail without expense. Give yourself a good couple of hours and try to get there early before the usual headphone brigade are there blocking the view! Many of the manuscripts are from the University collection, but there are also borrowings from the British Library, the Archbishop of Canterbury's Library and elsewhere. The later medieval and early Renaissance period is quite heavily represented, as one might expect. The show's chief focus is on the chemistry and provenance of pigments and materials used in book illumination but technique is also touched on. Iconographers will be interested to study the gradual development of different fleshpainting techniques, from the fully modelled style of the Byzantine period through to western experiments with pointillism, grisaille and tinted drawing. Other random gleanings that I shall follow up on my next trip: - Different ways of ruling the page: pricking, hardpoint, silverpoint, plummet. Medieval readers preferred their pages to be ruled and even drew in guidelines to the first printed books because the page looked naked without! So this business in calligraphy class about not showing the lines is a load of rubbish, ha! - Using black gesso under gilding for special effect. Must try, could look amazingly contemporary. - Indigo and woad are chemically indistinguishable when used as dyes or pigments. Western artists probably used woad. It will grow in the back garden, and I found someone on line who extracts and sells the pigment. - The fabled Tyrian purple, so expensive, was extracted from North Atlantic dogwhelks as well as from the Mediterranean murex. The farthest Scottish islands had a trade in it. On the other hand there was a cheap subsitute to be made from the turnsole plant or a variety of lichen, used on some of those glorious purple-dyed manuscripts. - Some French manuscript fragments c 1250 were described as having a 'stained glass palette', an artistic cross-fertilisation from the contemporaneous technological developments in coloured glass (remember that amazing Chartres Cathedral blue?). One of the pigments used was minium. I have always held off using minium (red lead) on the grounds of it being so toxic, but I suppose that's a bit daft given that I already use vermilion (mercury), white lead (for gesso) and the cadmiums. I am interested in this manuscript school, and up till now have had to guess at what pigments were used to achieve the effect.

|

The view from my deskCurrent work, places and events, art travel, and interesting snippets about Christian icons, medieval art, manuscript illumination, egg tempera,, gilding, technique and materials. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed