|

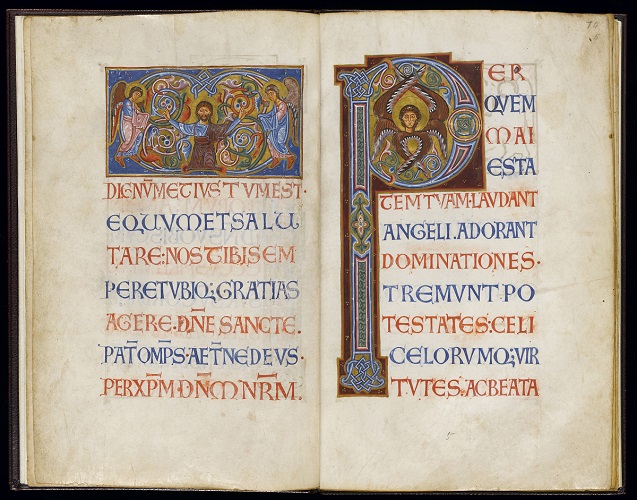

I was hard put to it to decide which beautiful picture to use as an illustration of my recent visit to this exhibition and eventually decided on this page from a Latin Kingdom of Jersusalem sacramentary, dated around 1128. I love it for the east-meets-west style of the icon panel, and the beautiful versal script. I am learning how to write versals at the moment, this is definitely one to add to the study list.

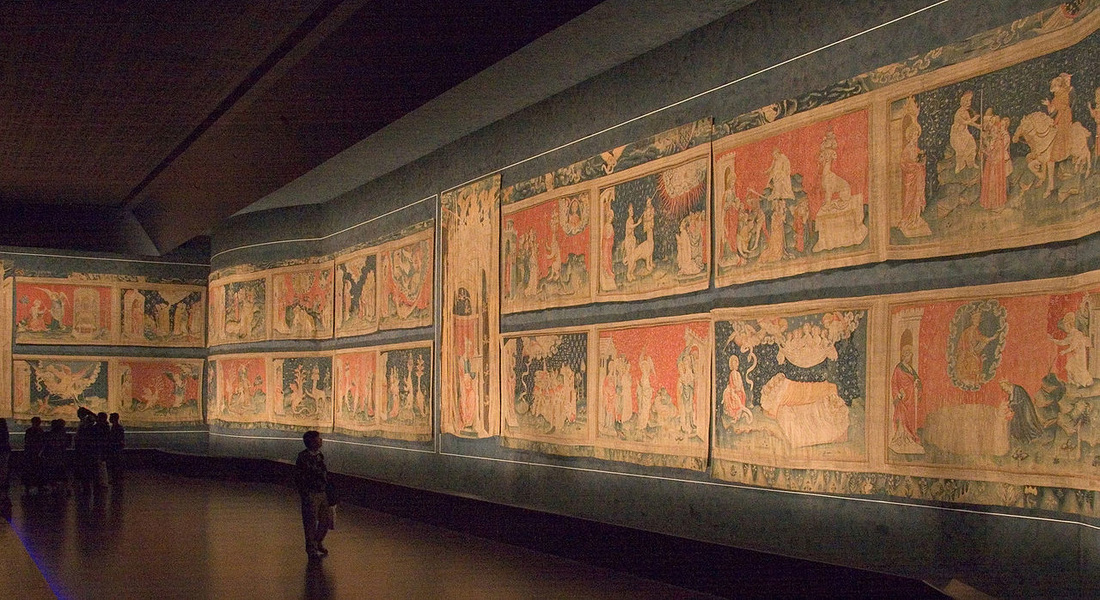

A must-go exhibition for iconographers, illuminators and scribes - on till December, so don't miss. Many of the manuscripts are in cases of course, giving the usual difficulty for close examination, but there are many cuttings framed on the wall which one can eyeball closely. There are also handy reference copies of the £30 exhibition catalogue lying everywhere, which means one can examine photographs and read up on detail without expense. Give yourself a good couple of hours and try to get there early before the usual headphone brigade are there blocking the view! Many of the manuscripts are from the University collection, but there are also borrowings from the British Library, the Archbishop of Canterbury's Library and elsewhere. The later medieval and early Renaissance period is quite heavily represented, as one might expect. The show's chief focus is on the chemistry and provenance of pigments and materials used in book illumination but technique is also touched on. Iconographers will be interested to study the gradual development of different fleshpainting techniques, from the fully modelled style of the Byzantine period through to western experiments with pointillism, grisaille and tinted drawing. Other random gleanings that I shall follow up on my next trip: - Different ways of ruling the page: pricking, hardpoint, silverpoint, plummet. Medieval readers preferred their pages to be ruled and even drew in guidelines to the first printed books because the page looked naked without! So this business in calligraphy class about not showing the lines is a load of rubbish, ha! - Using black gesso under gilding for special effect. Must try, could look amazingly contemporary. - Indigo and woad are chemically indistinguishable when used as dyes or pigments. Western artists probably used woad. It will grow in the back garden, and I found someone on line who extracts and sells the pigment. - The fabled Tyrian purple, so expensive, was extracted from North Atlantic dogwhelks as well as from the Mediterranean murex. The farthest Scottish islands had a trade in it. On the other hand there was a cheap subsitute to be made from the turnsole plant or a variety of lichen, used on some of those glorious purple-dyed manuscripts. - Some French manuscript fragments c 1250 were described as having a 'stained glass palette', an artistic cross-fertilisation from the contemporaneous technological developments in coloured glass (remember that amazing Chartres Cathedral blue?). One of the pigments used was minium. I have always held off using minium (red lead) on the grounds of it being so toxic, but I suppose that's a bit daft given that I already use vermilion (mercury), white lead (for gesso) and the cadmiums. I am interested in this manuscript school, and up till now have had to guess at what pigments were used to achieve the effect.

Upwardly mobile water for paint mixing, as supplied by my local pharmacy. Odd. But maybe this is what I've been missing all along...

|

The view from my deskCurrent work, places and events, art travel, and interesting snippets about Christian icons, medieval art, manuscript illumination, egg tempera,, gilding, technique and materials. Categories

All

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed