About my icons

Some time around the sixth century AD Christian artists switched from painting their sacred images in encaustic (wax) to egg tempera. No one knows why this happened, but the humble egg proved to be an immensely versatile and durable medium. The method of making an authentic icon has not changed much in the succeeding centuries. Strictly speaking an icon can be made in any worthy medium - fresco, carving, metalwork, illumination, even embroidery - since the word 'icon' just means 'image' in Greek. St Paul speaks of Jesus Christ being the true 'icon' of the invisible God (Colossians I, 15). In the Eastern Orthodox church icons are venerated as proxy for the saint depicted, and the place of images in liturgical ritual has been understood and fought for since earliest times. In the Western churches, Christians of all denominations are reaching a renewed understanding of the place sacred images have in personal devotions and public worship. In a word, the sacred images manifest to us the unseen presence of the company of heaven.

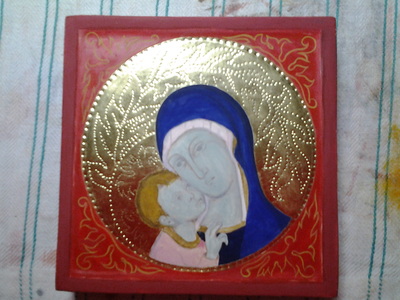

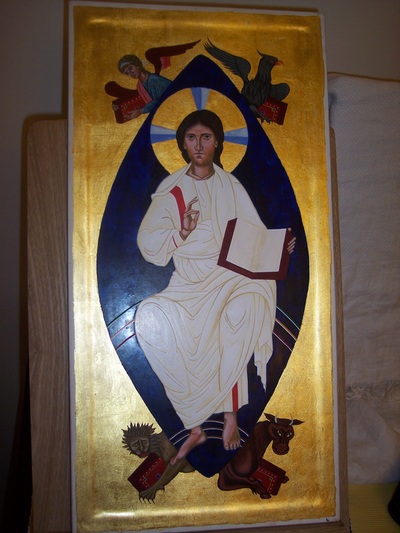

I don't care to talk a great deal about the devotional aspects of icon painting as it is easy to sound falsely pious, and I think that an icon, even more than a decorative painting, should do its own talking. Many people simply appreciate the intense colours and unsentimental aesthetic of this hagiographic art form. I research and plan my icons with great consideration, and study as many prototypes of different periods and in different media as possible, but to my mind icon painting is not about turning out accomplished copies of famous originals. It is more like writing a sonnet: there is freedom of expression to be found in the strict discipline of the established form.

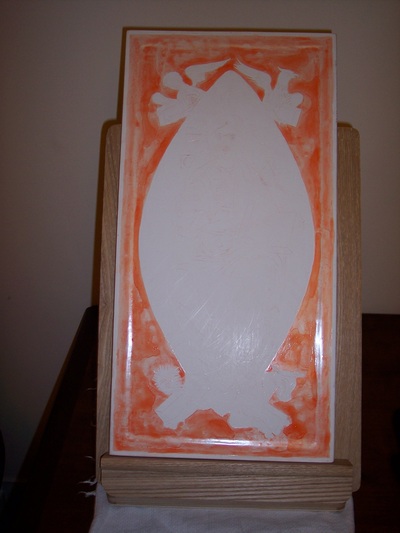

Every process involved in the actual making of an icon has both a practical and a symbolical purpose. For example, the effect of the central recess is both to protect the paint surface from wear and also to create an 'ark', or reserved space, for the sacred image. The egg used to bind the pigments is symbolic of new life, the transformative potential of life in the spirit and of the resurrection. Gold, the immortal metal, has a special significance expressing the radiance of God's uncreated light. Burnished gilding gives an icon a special radiance, especially in candlelight or when the sun catches it: a visual enactment of spiritual transfiguration. The systematic approach to painting the flesh, starting with the darkest tones and moving though the tones to purest white, mirrors the spiritual journey of the Christian from darkness into light. The choice of pigments also has symbolical meaning, whether one is choosing earth pigments such as umber and terre verte for the robes of a humble ascetic or vermillion and lapis lazuli with their esoteric significance. These are things for private meditation and I don't send my icons out with an explanatory essay: an icon speaks directly to the eye of the heart. Many things in iconographic art which seem unnatural - the stylisation, odd perspective, internal geometry, ritual gestures and stylisation - are devices to jolt us into a deeper reading of the piece, and to portray the transfigured existence of the holy person.

I don't care to talk a great deal about the devotional aspects of icon painting as it is easy to sound falsely pious, and I think that an icon, even more than a decorative painting, should do its own talking. Many people simply appreciate the intense colours and unsentimental aesthetic of this hagiographic art form. I research and plan my icons with great consideration, and study as many prototypes of different periods and in different media as possible, but to my mind icon painting is not about turning out accomplished copies of famous originals. It is more like writing a sonnet: there is freedom of expression to be found in the strict discipline of the established form.

Every process involved in the actual making of an icon has both a practical and a symbolical purpose. For example, the effect of the central recess is both to protect the paint surface from wear and also to create an 'ark', or reserved space, for the sacred image. The egg used to bind the pigments is symbolic of new life, the transformative potential of life in the spirit and of the resurrection. Gold, the immortal metal, has a special significance expressing the radiance of God's uncreated light. Burnished gilding gives an icon a special radiance, especially in candlelight or when the sun catches it: a visual enactment of spiritual transfiguration. The systematic approach to painting the flesh, starting with the darkest tones and moving though the tones to purest white, mirrors the spiritual journey of the Christian from darkness into light. The choice of pigments also has symbolical meaning, whether one is choosing earth pigments such as umber and terre verte for the robes of a humble ascetic or vermillion and lapis lazuli with their esoteric significance. These are things for private meditation and I don't send my icons out with an explanatory essay: an icon speaks directly to the eye of the heart. Many things in iconographic art which seem unnatural - the stylisation, odd perspective, internal geometry, ritual gestures and stylisation - are devices to jolt us into a deeper reading of the piece, and to portray the transfigured existence of the holy person.